Debunking Mike Archer’s ethical case (and bad statistics) for eating grass-fed meat.

Getting your protein from grass-fed beef does not spare more sentient animal lives than plant-based sources.

*Updated on 13/02/2025

Professor Mike Archer at the University of New South Wales has long accused vegetarians and vegans of having ‘more animal blood’ on their hands.1, 2 He claims that getting your protein from plants instead of (grass-fed) meats will end up costing the lives of at least 25 times more sentient animals. Although this claim has repeatedly gone viral as an ethical rebuke of plant-based diets, it is not empirically true. Not even close to what he figures.

Mike’s claim rests upon poor attempts to estimate and compare the number of sentient animals killed producing a kilogram of protein from wheat grain to grass-fed beef. There are two main problems with his approach. Firstly, his model grossly exaggerates how many rodent deaths occur in grain production, specifically during mouse plague abatement. Secondly, he fails to measure for animal life lost in grass-fed beef production beyond the slaughtered cattle, such as pest culling to protect grazing pastures.

Some simple corrections to Mike’s estimates reveal that even wheat grain – which is not the most efficient plant protein source available – will harm fewer sentient creatures than the most ‘ethical’ option available to meat eaters, grass-fed beef. His comparison of choice inadvertently ends up strengthening the ethical case for a plant-based diet.

Lives lost for 100kg of protein: Mike’s case for beef over wheat

Mike’s ethical argument for choosing meat over plants as a protein source hinges on a tally of the sentient animals killed producing 100kg of protein from wheat grain compared to grass-fed beef. He claims that the plant-based source kills upwards of 25 times more sentient creatures compared to the meat option. The statistic comes from his estimate of how many mice will be poisoned to death by grain growers during plague seasons in Australia.

According to Australia’s national science agency, the CSIRO, the country’s grain growing regions are hit by a mouse plague every four years on average.3 Assuming mice densities reach 500 per hectare in plague conditions and 80% are poisoned in baiting efforts, Mike figures that ‘[a]t least 100 mice are killed per hectare per year (500/4 × 0.8) to grow grain.’4 If a hectare yields 1.4 tonnes of grain and wheat is 13% protein, then growers can produce 182kg of wheat-based protein per hectare. To supply 100kg of protein, 0.55 hectares of cropland must be cultivated. Mike concludes that 55 mice are killed per 100kg of plant protein.

He then estimates that 2.2 grass-fed cows must be slaughtered to produce 100kg of protein. The calculation assumes an average carcase weight of 288kg, lean meat yield rate of 68%, and useable protein conversion rate of 23%. According to these measurements, a beef cow will yield 45kg of protein.

If it is correct that 100kg of protein from wheat kills 55 mice whereas grass-fed beef only involves 2.2 cattle slaughters, then choosing the plant-based option will entail 25 times more death. However, in neither of these cases are the estimates anywhere close to being accurate.

How Mike grossly exaggerates rodent deaths in grain production

Mike figures that each hectare of land on which grain is grown results in 100 mouse deaths annually. But this calculation hinges on a big assumption. As others have already pointed out,5 his model presupposes that every last hectare of cereal grain cropland is subject to mouse infestations and baiting. For Mike’s estimation is only correct if mouse plagues blanket a total area equivalent to 100% of Australia’s cereal croplands every four years. The same area must also be baited for the statistic to hold. Yet, this underlying assumption diverges far from the empirical reality.

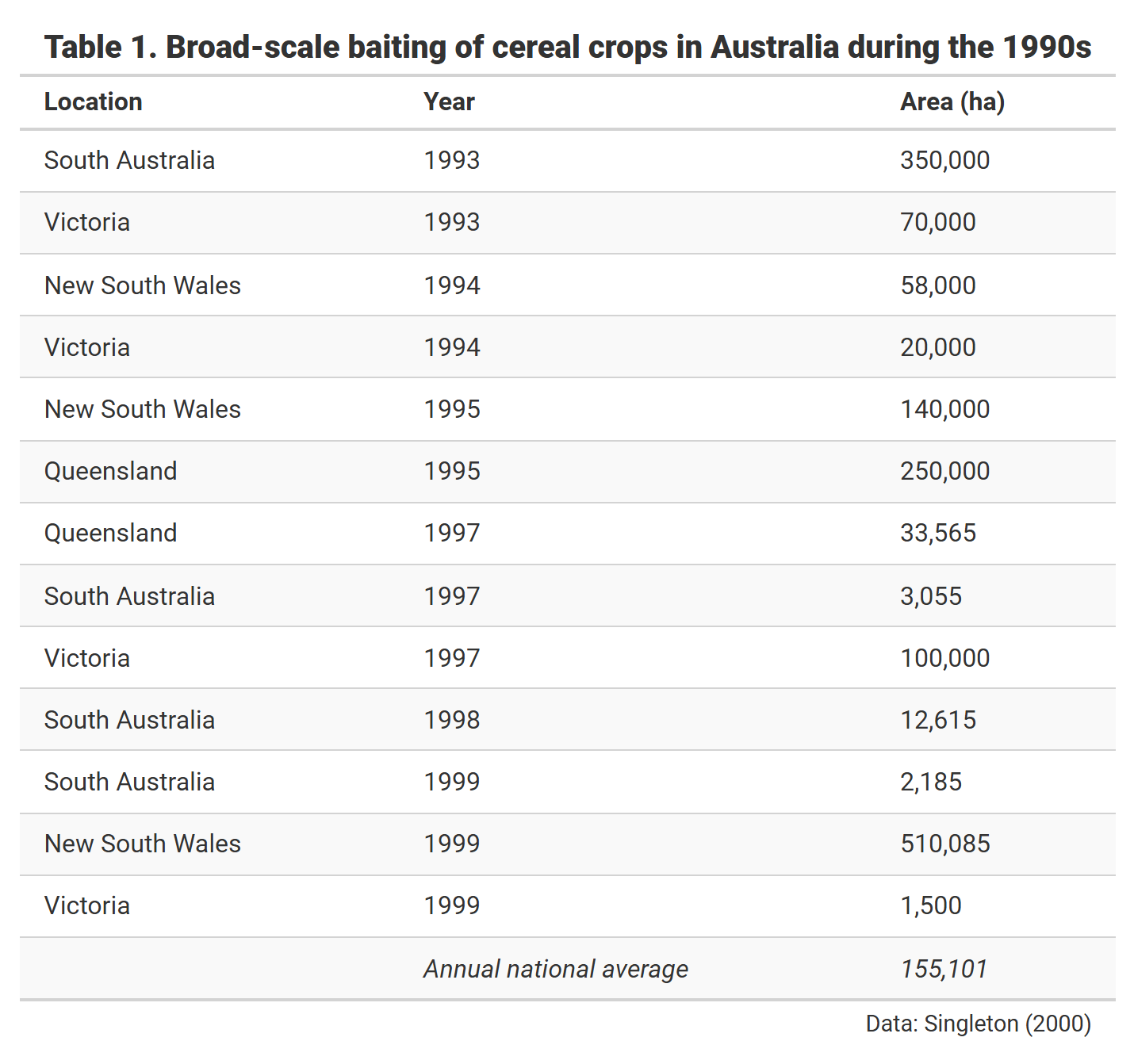

CSIRO research finds that ‘[a] mouse plague occurs somewhere in Australia once every four years’ (emphasis added).6 Somewhere is not everywhere. On average, mouse infestations only impact 100 to 500 thousand hectares of cropland annually.7 Data collected by CSIRO scientists on broad-scale rodent baiting in cereal-growing regions during the 1990s reveals that it spanned just 155 thousand hectares per year on average (see Table 1).8 Given that grain production9 in that decade covered 14 million hectares of cropland (see Table 2),10 it equates to only 1% of the total area being baited annually.

Mike’s case revisited: Wheat vs. beef in the 1990s

With the CSIRO baiting data, it is possible to test Mike’s viral claim that protein derived from wheat costs the lives of 25 times more sentient animals than beef. A control for the total area of cropland poisoned can be added to his model. It should provide an estimate that more closely aligns with reality. The sample period will span the 1990s given the available data.

To start off, in the 1990s, the average carcase weight of a beef cow was 215kg.11 At this weight, producing 100kg of protein requires the slaughter of 3 cows instead of the 2.2 in Mike’s original estimate. Also, whereas he relies on wheat yields of 1.4 tonnes per hectare, it averaged 1.7 tonnes in the 1990s.12 That works out to 223kg of wheat-based protein per hectare of cropland. Already, these new figures lower the estimated mouse deaths per 100kg of plant protein from 55 to 45, even without controlling for the total cropland area being baited.

For a claim of ‘100 mouse deaths per hectare per year’ to hold in the 1990s case, rodent baiting must have blanketed an area equivalent to 14 million hectares of cropland every four years, or 3.5 million hectares annually. But CSIRO data shows baiting only reached a yearly average 155 thousand hectares of Australia’s cereal-growing regions. Poisoning for mice occurred in just 4% of the cropland area that Mike has to assume to arrive at his original estimate.

If his model is left uncorrected in the 1990s case, the estimated mouse deaths from grain production will be 23 times higher than what it should be. When this discrepancy is corrected by controlling for the total area baited, the estimate of 45 mice being killed to produce 100kg of wheat-based protein is revised down to 2 mice. According to Mike’s own approach, then, few sentient animals would be killed producing 100kg of protein from wheat grain (at 2 deaths) compared to grass-fed beef (at 3 deaths).

Note that the CSIRO data covers baiting across Australia’s cereal growing regions in general, not exclusively wheat croplands. However, it is possible to repeat this exercise with the stricter assumption that baiting only occurred on areas dedicated to growing wheat grain. This would cover 9.2 million hectares of cropland during the 1990s. Using this basis, 3 mice would be poisoned per 100kg of wheat protein. Even in a harder test case, Mike’s claim that more sentient animals are killed producing protein from wheat than beef is still not supported, let alone it being 25 times more.

An alternative estimate of rodent deaths in grain production

Aside from Mike’s approach, another way to compare wheat and beef is to estimate what the upper limit of rodent deaths from grain cropping might reach under normal conditions. Now it would be a mistake to simply assume that most field mice die during grain production. On crop fields, mice reside in underground burrows during the day, exiting their nests at night when it is safer to forage. Disturbances to these mouse habitats from farming activities are limited by the ‘no-till’ practices that most Australian wheat growers follow for better crop yields.13, 14 Mouse burrows can be left intact year-round.15

For the sake of comparison, however, the following estimate will assume that 100% of field mice are killed in the cropping process. It would constitute the worst-case scenario. According to CSIRO researchers, there are normally 4 or 5 mice per hectare of cereal cropland.16, 17 With the 2010s serving as our reference period, wheat production averaged 2 tonnes of grain per hectare,18 meaning a maximum of 2 mice could potentially killed to make 100kg of wheat-based protein. In contrast, beef cattle carcase weights averaged 267kg over that decade,19 requiring that 2.4 cows be slaughtered to derive 100kg of protein.

It turns out in both normal and plague conditions rodent deaths per 100kg of wheat protein come nowhere close to the 55 mice estimated by Mike. In fact, even when assuming the worst-case scenarios for field mice during grain production, still it is found that sourcing protein from wheat rather than grass-fed beef will result in fewer sentient animals dying. The problems with his comparison do not end here either.

Grass-fed beef kills many more animals than just cows

When weighing the ethics of sourcing protein from wheat or beef, Mike’s work demonstrates the relevance of considering collateral animal deaths too. But while his comparison fixates on incidental killings tied to wheat production, it completely overlooks those that may be associated with grass-fed beef production. Rearing cattle involves activities that kill numerous sentient animals beyond the slaughtered livestock. This includes clearing forestland for grazing pastures, harvesting hay and silage crops for supplementary feeds, and culling pest species.

Example 1. Land clearing

Each year, around 100 million of Australia’s native wildlife are displaced, injured, or killed due to deforestation.20 Around three-quarters of land clearing throughout the country is driven by cattle grazing.21 In the case of Queensland, home to the nation’s largest beef cattle herd, around 38 million animals are killed annually from land clearing.22 Ninety-two per cent of land clearing across the state is undertaken to create pastures for grazing.23 Few are aware that the steak on their plate is behind most of the deforestation in Australia and the animal life that goes with it.

Example 2. Fodder crop production

Although grass-fed cattle do not eat grain, they are given hay and silage as supplementary feed. These fodder crops are grown and harvested across vast areas of cropland in Australia. In 2022, for instance, at an estimated value of $ 1.7 billion,24 hay and silage production covered 1.2 million hectares of cropland.25 That year, the average beef farm spent $23,630 of fodder.26 With 22,065 farms in total,27 beef industry spending on fodder crops amounted to $521 million. It could mean that hundreds of thousands of hectares of cropland are still being farmed to support grass-fed cows. Hence, rangeland beef might still be linked to crop deaths.

Example 3. Pest control

Livestock production involves the widespread culling of ‘pest’ species, including kangaroos and dingoes. But the most economically damaging species to beef cattle and sheep industries are rabbits.28 They compete with livestock for grazing pastures and have cost the industry billions of dollars. CSIRO researchers estimate that the economic benefits to the wool and meat industry from controlling rabbit numbers reaches at least $70 billion.29

Killing methods includes warren ripping, poisoning, trapping, and shooting. But the most lethal weapons deployed against rabbits are biocontrol agents, including the myxoma virus and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus, which can kill up to 85% of newborn rabbits in a single year.30 Together, the CSIRO and livestock industry moved to introduce and spread these viruses across Australia.31 Such efforts have proved effective at suppressing the rabbit population to a number far below its potential size.32

For some perspective on the possible scale of death entailed, Australia’s rabbit population reportedly stands between 150 to 200 million.33, 34 In favourable conditions, a female rabbit can produce five or more litters per year, totalling 50 to 60 offspring.35 This implies that many millions of ongoing rabbit deaths may be linked to grass-fed beef production via pest control efforts.

Overall, whatever the real body count of grass-fed beef production actually is, the above examples are enough to demonstrate the clear bias in Mike’s approach. He considers the animal life lost as collateral in crop farming, but fails to do so when it comes to livestock grazing. It has already been established the protein from wheat results in fewer sentient animal deaths than grass-fed beef even when only the slaughtered cattle are counted. What the section here indicates is that this difference between the two protein sources could be much larger in reality.

Beef cattle are actually the nation’s biggest grain guzzlers

By focusing on crop deaths, Mike tried to show there is ‘more animal blood’ spilt from getting your protein from grains instead of meat. He did this by selecting grass-fed beef, a grain-free livestock product, as the stand-in source for animal protein in his comparison. This is somewhat misleading, however, given that most animal proteins come from grain-intensive sources of meat, dairy, and eggs.

In fact, industry research reveals that the livestock sector is ‘by far the largest domestic market for Australian grain’36 and ‘a key driver of grain production.’37 Around two-thirds of Australia’s domestic consumption of grain goes towards fattening livestock.38 At an estimated 3 million tonnes, the beef cattle industry eats through the largest share.39, 40 This quantity matches the amount of grain milled into flour in Australia.41 Most of the beef found on major supermarket shelves is harvested from these grain-finished cows,42 whereas grass-fed beef is mainly sold to overseas buyers.

On the hypocrisy of ‘[t]he vegans and the animal liberationists and the animal rights people’

In his attempt to rebuke ‘[t]he vegans and the animal liberationists and the animal rights people,’ Mike pushed the empirical claim that a plant-based diet ends up killing more sentient animals than a diet that permits rangelands-produced red meat as a protein source.43 Although the Professor arrived at this conclusion having supposedly, in his words, ‘number-crunched in every conceivable way,’ a fact-check of some key assumptions reveals that Mike’s numbers are way off mark.44 Even when factoring in rodent deaths during crop production, fewer sentient animals will be killed producing protein from wheat compared to grass-fed beef, the sacred cow of the ‘ethical’ meat-eater.

But the Professor will still protest that animal rights advocates ‘can’t possibly get away from the fact that our vegan and vegetarian diets involve the deaths of wonderful sentient animals.’45 He advises us to ‘stop being hypocritical’ and ‘just accept the fact that in order to survive, other animals are going to die.’46 Here Mike displays a shallowness when comes to thinking about the morality of killing of animals.

Let us begin with the idea that it is okay to farm animals simply because of this alleged hypocrisy from vegetarians and vegans. Few would accept this line of reasoning were it applied to other moral concerns. Consider the exploitation of children, which still takes place across supply chains for consumer products that Australians regularly buy, from Congolese child miners toiling ‘in slave-like conditions’ to extract the cobalt used in our battery-powered devices47 to Bangladeshi slum kids working full-time hours in unsafe garment factories to stitch together our clothing.48 Almost nobody can ‘possibly get away from the fact’ of financially contributing to child exploitation in some way.

Based on Mike’s standards, regardless of how inadvertent, indirect, or marginal this contribution may be, it makes it hypocritical for nearly anybody to criticise or prevent the exploitation of children. It should just be accepted as a fact of life, so it seems. Of course, most would reject such a conclusion; presumably, Mike would too. Similarly, that vegetarians and vegans may still be loosely linked to some animal deaths is not grounds to dismiss their moral case against the consumption of animal proteins. Rather, the case should to be judged on its own merits.

Now with that said, the accusation of moral hypocrisy can be addressed directly. In levelling this charge, Mike seems to view the killing of animals in slaughterhouses and crop fields as morally equivalent acts. It is what leads him to evaluate the ethics of farming grains or livestock in terms of a single metric: a tally comparing the number of sentient lives taken for a kilo of protein. This gives consideration to the scale at which animals are being killed, but none to why it is happening. His is an approach to morality that weighs outcomes but ignores intentions.

It is an oversight on Mike’s part. In conventional morality and law, motive and intent are relevant factors when judging someone’s innocence or guilt. This is owing to our moral agency. Normal adults are capable of understanding and following principles and rules that distinguish right from wrong. Whether they choose to comply is another matter. But it is this capacity for doing so which gives them some degree of responsibility for the decisions they make and acts they carry out. By knowing the motive and intent that lie behind a person’s chosen course of action, we can determine the reason why they did. Depending on what this reason indicates, we may potentially hold them to account. In a criminal trial, for example, a conviction involves demonstrating that the defendant’s harmful act, actus reus, was paired with a guilty mind, mens rea.

To illustrate how paramount motive and intent are in moral and legal matters, consider the killing of civilians in combat. An unfortunate but predictable reality of military operations is that innocents will be killed in the crossfires. However, these incidental killings of civilians, which are foreseeable but unintended, are morally and legally distinguished from attacks that deliberately target noncombatants.49 The former situation is collateral damage; the latter is designated as terrorism or worse.

The fact that collateral damage is an acknowledged reality of war by no means makes terror attacks permissible. But neither does it prohibit armies from waging war when there is just cause (e.g., self-defence), despite endangering civilian lives. For although collateral damage involves the killing of innocents, only terror attacks are interpreted as treating civilian lives as a disposable means to a policy end, thereby, rendering such acts impermissible. By the laws of war, there is only an obligation that armies take measures to mitigate collateral damage when conducting strikes on military targets. Without considering the motive and intent of the combatants, however, such moral and legal distinctions on civilian killings could not be drawn.

This example is instructive for dealing with the issue of animal deaths in agriculture. If we consider motive and intent, some important moral distinctions can be drawn between an animal killed on the crop field or in the slaughterhouse. To begin, it is necessary to briefly review why ‘the animal rights people’ believe that it is wrong to farm livestock for food and fibre. Though Mike did not bother to check, the reasoning goes deeper than the immediate fact that an animal is being killed.

Fundamentally, it is a matter of valuation. Those ‘animal rights people’ take issue with how society values animals exclusively in instrumental terms. From being classed as ‘things’ in legal codes or listed as ‘assets’ on balance sheets, our institutions are designed so as to recognise nothing inherently special in animals. Rather, an animal’s worth is wholly derived from serving as a means to human ends. They are like a tool or resource to us. This view is entrenched via property rights, whereby the law empowers individuals and corporations to own, use, trade, and even destroy animals to gain material benefits. It turns animals into livestock, enabling entire industries to be built upon their commercial exploitation.

Livestock are valued differently by ‘the animal rights people,’ however. Given their ability to perceive and feel, livestock are seen as possessing a trait or quality that humans value for its own sake in themselves and each other. Put simply, there is inherent worth in these animals. As they have value that goes beyond being an instrument to human ends, to class such animals legally as ‘things’ or commercially as ‘assets’ is to commit a category error. Accordingly, it is seen as illegitimate to subject them to property rights claims and improper treat them as resources for consumption. This line of reasoning is what leads ‘the animal rights people’ to morally oppose the practice of farming livestock, including their slaughter specifically.

Although animals are killed in crop farming, the activity is not predicated on treating them as a commodity. There is no requisite intent to treat animals as a mere instrument for our ends. Rather, the harm done to animals is incidental to an otherwise legitimate enterprise, the growing of grains and other staple foods. Moreover, the plant proteins supplied from these crops provides a substitute to animal proteins from livestock.

Looking more closely, when crop farming results in animal deaths, it is usually one of two scenarios. The first is that it happens unintentionally by chance in the course of regular activities, like ploughing or harvesting. The other situation is that it occurs deliberately for pest control, such as the poisoning of mice during plagues which Mike highlights. But in the latter case, the motive is defensive in nature. Were we to allow animals to damage staple crops, like wheat, then our food security is threatened.

While these instances of killing may be permissible by way of intention, it is nevertheless the case that these animals have inherent value and their interests are being harmed by our acts. As in the case of collateral damage in warfare, we are thereby obliged to take measures to lower the harm done to innocents where possible. In crop farming, there has been some headway already made in this endeavour. The spread of no-till farming methods amongst grain growers, which happens to cause less damage to mouse habitats, is one example. Another is the development of non-lethal alternatives to pesticides and baits, such as the use of wheat germ oil to camouflage the scent of wheat seeds, which has been shown to inhibit mice from targeting wheat crops in recent trials.50

Overall, the fact that we cannot be morally pure in our dealings with animals is not grounds for being morally evil towards them. In concrete terms, that crop farms kill animals is no excuse to farm animals to kill. And, contrary what Mike preaches, the slaughter of livestock should not just be accepted as a fact of life. Annually, nearly 800 million livestock animals are sent to the slaughterhouse in Australia.51 If we count the world, that figure soars a hundredfold to over 80 billion slaughters.52 That is a lot of lives that could and should otherwise be spared.

A final remark

In the closing paragraph of his article, Professor Mike Archer declared that ‘[t]he challenge for the ethical eater is to choose the diet that causes the least deaths’ to sentient animals.53 However, contrary to his calculations, it turns out that even a protein source like wheat results in fewer sentient animal deaths compared to the best-case options available from meat, such as grass-fed beef. This point becomes more evident when one counts all the other animals killed during land clearing, crop farming, and pest culling to support cattle grazing. In terms of saving ‘sentient lives,’ following a plant-based diet remains the obvious choice for the ethical eater.

At your next meal, make sure to order the vegetarian/vegan option.

Notes:

Archer, Mike, “Ordering the vegetarian meal? There’s more animal blood on your hands,” The Conversation, December 16, 2011, https://theconversation.com/ordering-the-vegetarian-meal-theres-more-animal-blood-on-your-hands-4659

Archer, Mike, “Ordering the vegetarian meal? There’s more animal blood on your hands,” SBS News, April 23, 2019, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/insight/article/ordering-the-vegetarian-meal-theres-more-animal-blood-on-your-hands/dyyi45f5r

Singleton, Grant R., Peter R. Brown, Roger P. Pech, Jens Jacob, Greg J. Mutze, and Charles J. Krebs. “One Hundred Years of Eruptions of House Mice in Australia - a Natural Biological Curio.” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 84, no. 3 (2005): 617–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00458.x

Archer, Mike, “Ordering the vegetarian meal? There’s more animal blood on your hands,” SBS News, April 23, 2019, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/insight/article/ordering-the-vegetarian-meal-theres-more-animal-blood-on-your-hands/dyyi45f5r

Animal Liberation South Australia, “Archer’s dodgy claims III … mouse deaths,” August 3, 2014, http://www.animalliberation.org.au/blog/2014/9/1/archers-dodgy-claims-iii-mouse-deaths

Brown, Peter R., Grant R. Singleton, Roger P. Pech, Lyn A. Hinds, and Charles J. Krebs, “Rodent outbreaks in Australia: mouse plagues in cereal crops,” in Rodent Outbreaks: Economy and Impacts, ed. Grant R. Singleton, Steve R. Belmain, Peter R. Brown, and Bill Hardy (International Rice Research Institute, 2010), 225.

McLeod, Ross, and Andrew Norris, Counting the Cost: Impact of Invasive Animals in Australia, 2004. (Canberra: Cooperative Research Centre for Pest Animal Control, 2004), 9.

Singleton, Grant R. 2000. “Ecologically-Based Rodent Management Integrating New Developments in Biotechnology,” paper presented at Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference 19, California. https://doi.org/10.5070/V419110207

Australia’s cereal crop consists of wheat, oats, barley, triticale, sorghum, rice, and maize.

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Australian crop report: December 2024, No. 211 (December 3, 2024), distributed by ABARES: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://doi.org/10.25814/a84a-mb52

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Agricultural commodity statistics 2023 (September 24, 2024), distributed by ABARES: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://doi.org/10.25814/4qkr-xr04

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Australian crop report: December 2024, No. 211 (December 3, 2024), distributed by ABARES: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://doi.org/10.25814/a84a-mb52

Bellotti, B, and J.F Rochecouste. “The Development of Conservation Agriculture in Australia—Farmers as Innovators.” International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2, no. 1 (2014): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30011-3

Singleton, Grant R., Peter R. Brown, Roger P. Pech, Jens Jacob, Greg J. Mutze, and Charles J. Krebs. “One Hundred Years of Eruptions of House Mice in Australia - a Natural Biological Curio.” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 84, no. 3 (2005): 619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00458.x

Vincent, Michael, “Mouse plague: Bait sales soar as famers grapple with population explosion,” ABS News, June 30, 2017, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-30/mouse-plague/8662842

BBC News, “Australian conditions ‘favourable’ for mouse plague, scientists warn,” January 17, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-38645836

Charlton, Corey, “Inside the mystery mice plagues that destroy rural Australia every four years,” news.com.au, January 16, 2019, https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/health/inside-the-mystery-mice-plagues-that-destroy-rural-australia-every-four-years/news-story/acfcabf428bf6070015af1dc3a286e7d

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Australian crop report: December 2024, No. 211 (December 3, 2024), distributed by ABARES: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://doi.org/10.25814/a84a-mb52

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Agricultural commodity statistics 2023 (September 24, 2024), distributed by ABARES: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://doi.org/10.25814/4qkr-xr04

Taylor, Martin, Mandy Paterson, and Tessa Derkley, The ongoing animal welfare crisis from deforestation in Australia (Greenpeace and RSPCA, 2024), 9, https://www.greenpeace.org.au/static/planet4-australiapacific-stateless/2024/07/a7936650-rspca-greenpeace-deforestation-report-2024-web.pdf

vstats, “Update: Animal agriculture drives 79% of deforestation in Australia,” January 31, 2023, https://vstats.substack.com/p/update-animal-agriculture-drives

Cogger, Hal, Chris Dickman, Hugh Ford, Chris Johnson, and Martin Taylor, Australian animals lost to bulldozers in Queensland 2013-15 (WWF-Australia, 2017),

Queensland Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Land cover change in Queensland 2015-16: Statewide Landcover and Tree Study (SLATS) report (2017), 23, Table 5, https://apo.org.au/node/113241

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Value of Agricultural Commodities Produced, Australia, (January 17, 2023), distributed by ABS, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/agriculture/value-agricultural-commodities-produced-australia/2021-22

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Agricultural Commodities, Australia, (January 17, 2023), distributed by ABS, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/agriculture/agricultural-commodities-australia/2021-22#data-downloads

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Farm Data Portal (December 3, 2024), distributed by ABARES: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/data/farm-data-portal#daff-page-main

Ashton, Dale, Quin Welford-Brink, and Jay Ryder. Financial performance of livestock farms (ABARES and Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, 2024), https://daff.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/search/asset/1035924/0

Verbeek, Birgitte, Ecology and Management of Vertebrate Pests in NSW, ed. Lynette McLeod (New South Wales Department of Primary Industries, 2018), 22, https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/439200/Ecology-and-Management-of-Vertebrate-Pests-in-NSW-March-2018-web.pdf

Cooke, Brian, Australia’s War against Rabbits: The Story of Rabbit Haemorrhagic Diseases (CSIRO Publishing, 2014), 112.

Department of the Environment and Energy, Background document: Threat abatement plan for competition and land degradation by rabbits (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2016), 19, https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/tap-rabbit-background-2016.pdf

Cooke, Brian, “Controlling rabbits: lets not get addicted to viral solutions,” The Conversation, March 8, 2012, https://theconversation.com/controlling-rabbits-lets-not-get-addicted-to-viral-solutions-5701

Cox, Tarnya, Tanja Strive, Greg Mutze, Peter West, and Glen Saunders, Benefits of Rabbit Biocontrol in Australia (Orange: Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre, 2013), 15, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281419596_Benefits_of_rabbit_biocontrol_in_Australia

Taggart, Pat and Brian Cooke, “Don’t underestimate rabbits: these powerful pests threaten more native wildlife than cats or foxes,” The Conversation, October 21, 2021, https://theconversation.com/dont-underestimate-rabbits-these-powerful-pests-threaten-more-native-wildlife-than-cats-or-foxes-168288

Agence France-Presse, “Cute But Calamitous: Australia Struggles with Rabbit Numbers,” VOA News, September 3, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/cute-but-calamitous-australia-struggles-with-rabbit-numbers-/7252586.html

Centre for Invasive Species Solutions, Benefits of Rabbit Biocontrol in Australia: an update (Canberra: Centre for Invasive Species Solutions, 2021), 5, https://invasives.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Benefits-of-Rabbit-Biocontrol-web.pdf

Spragg, John. Australian Feed Grain Supply and Demand Report 2018 (Poowong: Feed Grain Partnership and JCS Solutions Pty Ltd, 2018), 22, http://www.feedgrainpartnership.com.au/items/1023/FGP%20Feed%20Grain%20Supply%20and%20Demand%20Report%20Oct%202018.pdf

Grains Research and Development Corporation, “Growing regions,” 2021, https://grdc.com.au/about/our-industry/growing-regions

Spragg, John. Australian Feed Grain Supply and Demand Report 2018 (Poowong: Feed Grain Partnership and JCS Solutions Pty Ltd, 2018), 4, http://www.feedgrainpartnership.com.au/items/1023/FGP%20Feed%20Grain%20Supply%20and%20Demand%20Report%20Oct%202018.pdf

On the assumption that grain inputs make up 78% of the 3.9 million tonnes of grain-based feed that beef cattle consumed in 2018.

Spragg, John. Australian Feed Grain Supply and Demand Report 2018 (Poowong: Feed Grain Partnership and JCS Solutions Pty Ltd, 2018), 23, http://www.feedgrainpartnership.com.au/items/1023/FGP%20Feed%20Grain%20Supply%20and%20Demand%20Report%20Oct%202018.pdf

Spragg, John. Australian Feed Grain Supply and Demand Report 2018 (Poowong: Feed Grain Partnership and JCS Solutions Pty Ltd, 2018), 4, http://www.feedgrainpartnership.com.au/items/1023/FGP%20Feed%20Grain%20Supply%20and%20Demand%20Report%20Oct%202018.pdf

Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Cattle and beef market study – Final report (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2017) 21, Box 1.1, https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/ACCC%20Cattle%20and%20beef%20market%20studyFinal%20report.pdf

Archer, Mike, “Mice: the biggest losers with vegetarianism,” ABC, May 1, 2013, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/scienceshow/mice-the-biggest-losers-w-vegetarianism/4660498

Archer, Mike, “Mice: the biggest losers with vegetarianism,” ABC, May 1, 2013, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/scienceshow/mice-the-biggest-losers-w-vegetarianism/4660498

Archer, Mike, “Mice: the biggest losers with vegetarianism,” ABC, May 1, 2013, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/scienceshow/mice-the-biggest-losers-w-vegetarianism/4660498

Archer, Mike, “Mice: the biggest losers with vegetarianism,” ABC, May 1, 2013, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/scienceshow/mice-the-biggest-losers-w-vegetarianism/4660498

Lavoipierre, Angela, Stephen Smiley, and Lin Evlin, “Children mining cobalt in slave-like conditions as global demand for battery material surges,” ABC News, July 25, 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-07-25/cobalt-child-labour-smartphone-batteries-congo/10031330

Safi, Michael, “Child labour ‘rampant’ in Bangladesh factories, study reveals,” The Guardian, December 8, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/dec/07/child-labour-bangladesh-factories-rampant-overseas-development-institute-study

Amnesty International, “Armed conflict,” 2024, https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/armed-conflict/

Parker, Finn C. G, Catherine J. Price, Jenna P. Bytheway, and Peter B. Banks. “Olfactory Misinformation Reduces Wheat Seed Loss Caused by Rodent Pests.” Nature Sustainability 6, no. 9 (2023): 1041–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01127-3

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Australian commodities: December quarter 2024 (December 3, 2024), distributed by ABARES: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://doi.org/10.25814/82b5-tg66

Rosado, Pablo, “More than 80 billion land animals are slaughtered for meat every year,” Our World in Data, May 31, 2024, https://ourworldindata.org/data-insights/billions-of-chickens-ducks-and-pigs-are-slaughtered-for-meat-every-year

Archer, Mike, “Ordering the vegetarian meal? There’s more animal blood on your hands,” SBS News, April 23, 2019, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/insight/article/ordering-the-vegetarian-meal-theres-more-animal-blood-on-your-hands/dyyi45f5r

Thanks for a comprehensive analysis. Other than uncertainty around the numbers of mice killed on wheatfields during plagues (I have read that estimates can run to many thousands per hectare, and if we are considering a typical hectare over the course of a whole year during a plague season, could it be even more?), I think this shows Archer's claims to be on shakey ground.

That said, is there an easier way to evaluate the proposition? I'd say this.

Estimates for cropland footprint for a typical vegan diet seem to fall around 0.15-0.18 hectares. For a typical non-vegan diet, it seems to be somewhere around 0.30 hectares. See for example Peters et al 2016.

That suggests that whatever average rate of animal deaths are per hectare, the vegan diet causes fewer. Add to whatever toll we can derive from that, the number of animals killed for food (and indirect associated deaths such as seafood bycatch), plus the animals killed by farmers on the 0.74 hectares of grazing land used for the typical diet, and the vegan diet does seem to come out notably ahead.

Not always, I guess. But well enough on average.

If you think anything doesn't have feelings then I think you don't have feelings. We have a dconmon ancestor with anything that can be eaten, and many things that can't too. Everything that is alive has a common ancestor with us. Plants just a little further than humans but like us they breathe oxygen after being cut off their umbilical cord vine